Fig. 1: Google Books Ngram data for the queries “Christmas” and “divorce” in the English corpus between 1850 and 1950. The two data series show a high Pearson correlation coefficient of R=0.93.

The plot above shows that “Christmas” and “divorce” are mentioned in books with frequencies that show very similar trends over a period of 100 years. So does this mean that people planned to divorce a lot around Christmas? Or did the relaxed atmosphere around Christmas with the whole family coming together in a crowded house full of alcoholic beverages somehow lead to a lot of divorces? Or is Christmas actually a holiday of divorce?

Looking only at these data might lead you to wrong conclusions about causal relationships between highly correlated data series such as the ones above. Correlation (e.g., two events occurring together), however, does not imply causation. (i.e., one is the cause of the other).

Some such cum hoc ergo propter hoc (Latin for “with this, therefore because of this”) fallacies can quite easily be excluded using common sense (Christmas was clearly not established to celebrate divorces) but others are a lot trickier (this article). Additional experimentation and data can help to exclude some possible causal relationships or add additional evidence supporting others.

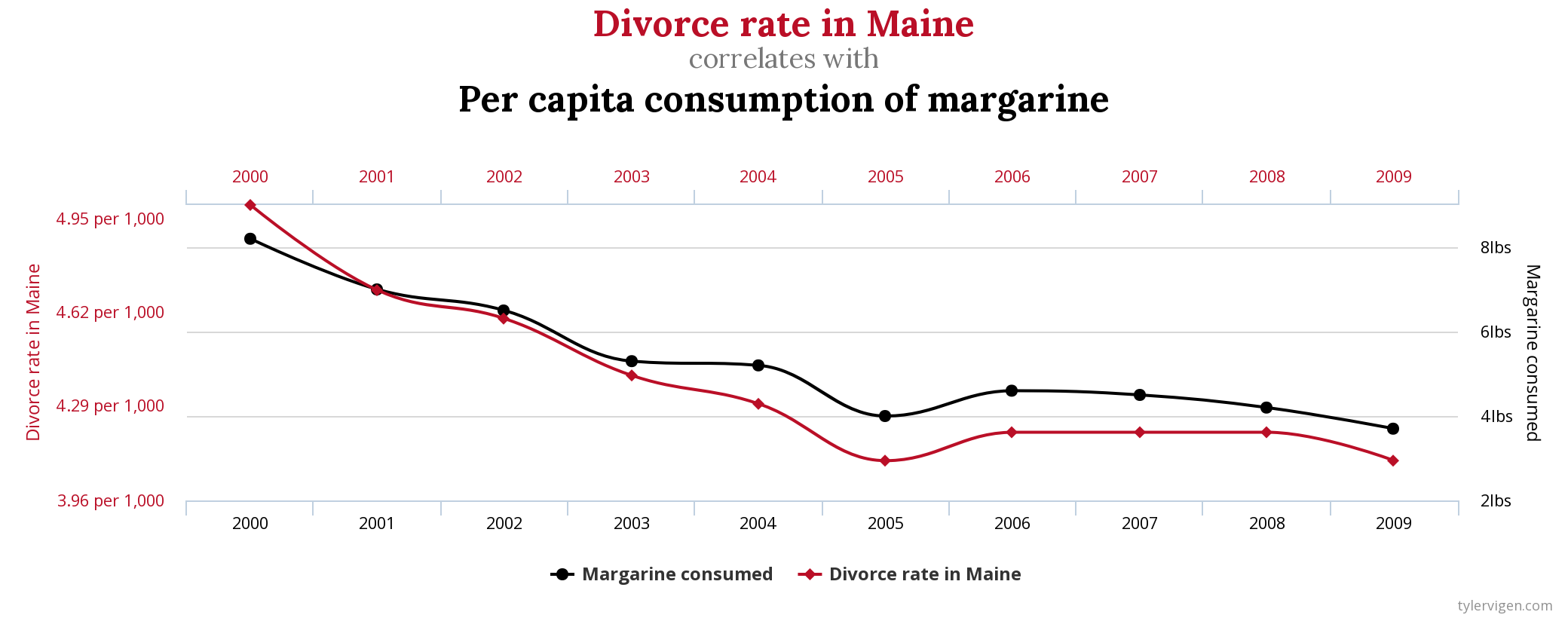

Other examples of so-called “spurious correlations” (i.e., correlated events without a direct causal relationship) are presented on this recommended website. There, it is for example uncovered that the consumption of margarine is correlated with the divorce rate in the US federal state of Maine. But it might be rather easy to see that there is no real causal relationship between these two events.

A more serious discussion of the often-made mistake to conclude a causative relationship from highly correlated data can be found in this recommended video from Khan academy. Here, it is discussed whether eating breakfast could be a possible solution to teen obesity?

So you might want to be extra careful to not mix up correlation and causation, which are indeed two very different things. Confusing them leads to a lot of false claims that are seemingly supported by real data.

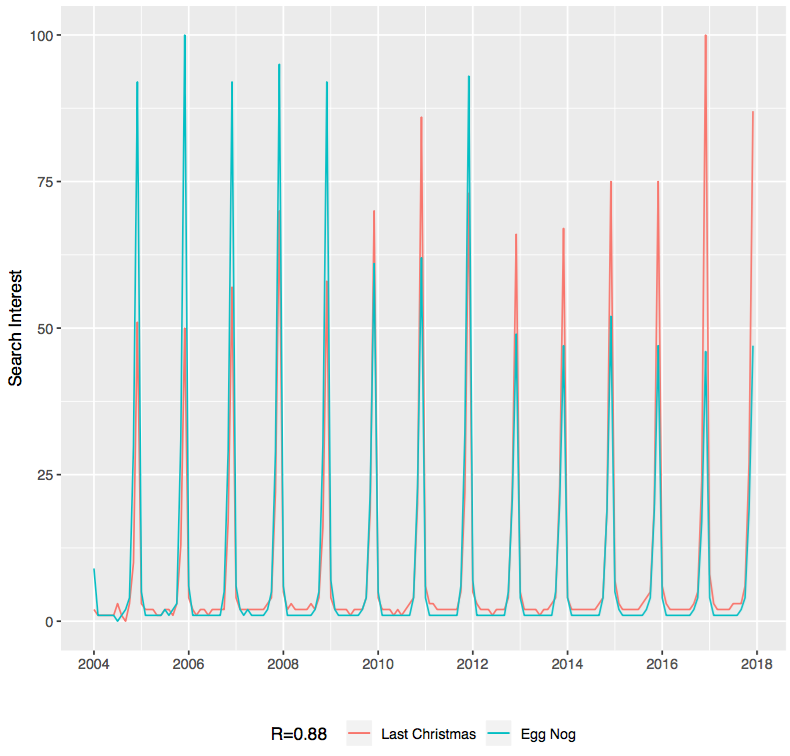

One thing, however, is for sure: Christmas is also (highly correlates with) Egg Nog season. You might want to do some experimentation yourselves to work out whether there is a causal relationship between the two ;)

Cheers!

Ps: The R scripts that were used to query Google ngrams/ trends and plot the respective correlations can be found in our Github repository. Feel free to use them to search for other (spurious) correlations or have a look at the Google correlate project.

About the authors

Niko Popitsch studied computer science and molecular biology and currently works at the Children’s Cancer Research Institute where he is applying innovative genomics methods to paediatric cancer datasets to better understand and fight childhood cancer.

Anna Köferle studied Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry at the University of Oxford and then completed a PhD at University College London. She is interested in gene regulation, epigenetics and everything to do with the gene editing tool “CRISPR”. Since starting as a researcher at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich two years ago, she has also developed some interest in topics relating to neurobiology.

Lukas Hutter studied chemistry in Graz and Systems Biology at the University of Oxford. He is a co-founder of Biotop and works as a teacher in Villach.